By George Mitrovich

30 September 2003

Preface:

On Friday morning, September 26, I learned of George Plimpton’s death. That day I wrote a tribute to him concerning experiences we had shared. After it was sent by e-mail to family and friends, more experiences came flooding back. I subsequently revised and expanded my tribute.

Many people knew George Plimpton longer than me – and better. For instance, Peter Matthiessen, one of the founding editors of The Paris Review, knew George for 70 years. I knew George for more than 25, but we lived a continent apart. If I was fortunate I saw him several times a year, but I did not have the opportunity to see him frequently, as did many of his friends. Therefore, whenever I saw him, I treasured the moment, and absorbed the experience.

I have here recounted some of those times. In the hands of others, truly gifted in the art of writing, they would have captured him in ways I am not capable of, my skills unequalled to theirs. I suffer no illusions about this. They, like George, are “out of my league.“

But on the justification for revising and expanding, here it is: George told me once that when Ernest Hemingway wrote “For Whom the Bells Toll”, he rewrote the last sentence of the last paragraph of the last chapter, 117 times!

A Great Man

It was with a heavy heart, deep sadness, and more than a few tears, I learned George Plimpton had passed away.

It was shocking news. Just the day before his death I had a lengthy conversation with the Great Man – as he will forever be known to me, for if anyone I have ever known deserved the distinction of greatness, it was George Ames Plimpton. It's true he often remarked, following one of my introductions of him, that I was America's uncrowned champion in the use of “hyperbole." But my judgment as to his greatness will stand the test of time – for the term “greatness” applies to more than political leaders, military heroes, film or sports stars.

I had the pleasure of his friendship for more than 25 years. More than 20 times he spoke to The City Club of San Diego and The Denver Forum, a number exceeded only by Dick Reeves. (Like Reeves, and the other guests of The City Club and The Forum over these 29 years, he never received a single honorarium.) And while I heard most of his stories from his "participatory" journalism days many times, each retelling elicited from me the same results – waves of laughter.

He was one of the best storytellers who ever graced a platform, stood behind a podium, or spoke into a microphone. Only Alan Simpson, the former United States Senator from Wyoming, was George’s equal in front of an audience; assuming, that is, you consider laughter one of God’s gifts to humankind.

A Day at Fenway Park

Just this past May, prior to a Boston Red Sox game at Fenway Park against Cleveland, I introduced George to a small audience of invited guests (George was a Red Sox fan of long standing). In making the introduction I said, "While our special guest has many great distinctions and accomplishments, I have but one. I have had the honor of introducing him more than anyone else in America." To others that may seem insignificant, but to me, be assured, it was not.

Just this past May, prior to a Boston Red Sox game at Fenway Park against Cleveland, I introduced George to a small audience of invited guests (George was a Red Sox fan of long standing). In making the introduction I said, "While our special guest has many great distinctions and accomplishments, I have but one. I have had the honor of introducing him more than anyone else in America." To others that may seem insignificant, but to me, be assured, it was not.

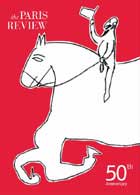

Each person who heard George speak that day was given an autographed copy of the anthology that celebrates his greatest achievement – the 50 years he edited The Paris Review, the world's finest literary quarterly. It is a gift each person shall now treasure, even more. (I am grateful that Mark and Tim Mitrovich were there that day, to see and visit with George, and to have received signed copies of the anthology.)

Each person who heard George speak that day was given an autographed copy of the anthology that celebrates his greatest achievement – the 50 years he edited The Paris Review, the world's finest literary quarterly. It is a gift each person shall now treasure, even more. (I am grateful that Mark and Tim Mitrovich were there that day, to see and visit with George, and to have received signed copies of the anthology.)

Larry Lucchino, the Red Sox President, gave George a team jacket – bright red. He wore it at the game, on the plane back home to NYC, and was seldom separated from it thereafter. We had many chats during the 2003 baseball season about the team's fortunes, always punctuated by a measure of angst (it’s part of the DNA of being a Red Sox fan). He would have known before he died that the Red Sox had become the 2003 American League's Wild Card Champions. He would have been thrilled.

Democratic National Convention

In 1980 I was a delegate for Ted Kennedy at the Democratic National Convention in New York. On the second night of the Convention, I invited George to join me, having previously arranged for the necessary credentials. We sat with the California delegation on the floor of Madison Square Gardens. He told me it was his first Convention. I was quite taken aback. I thought, surely this man who had done everything, must have previously attended a national political convention. He insisted he had not.

During a lull in the Convention proceedings (there are many such “lulls”), we went looking for a hot dog. Wandering around one of the Garden’s endless hallways in search of a refreshment stand, we ran into Mayor Koch and his security detail. The Mayor saw George and said in a loud voice, “George, have you seen your father?” George’s father, Ambassador Plimpton, had just returned from a trip to China, and the Mayor and the Ambassador had visited. Sheepishly, George told the Mayor he hadn’t. The Mayor said, in an even louder voice, “George, see your father!” I think George was embarrassed, but I found the scene hilarious. How many times in one’s life does the Mayor of New York tell you, “See your father!”

I have one other memory of that week in New York. George and Dick Tuck, the most famous political prankster in American history, held a party in my honor at on the Sunday night before the Convention began. It was quite a dazzling party, and despite being up against Kay Graham’s Washington Post/Newsweek party (always the number one party ticket at any national political convention, a remarkable group of people turned up at George’s East Side brownstone. In fact, a writer from The New Yorker found sufficient material to include a little note about the party in the magazine. I found it all quite amazing, that so many people would show up at a party for a guy from San Diego.

It wasn’t until several years later I learned the truth (at least Dick Tuck’s version of the truth). It wasn’t really a party in my “honor”, but one that was billed as a party for Dick and George. By then it didn’t matter, since I had a really great time at “my” party. However, If I were more insightful I might have realized much earlier the truth about the party, of why people came. How? The fact that The New Yorker article the following week made not one reference to me, the ostensible guest of honor.

George was a great party giver and people loved going to his parties, less for the quality of the food and wine than the quality of the people who came. To be at a party at George’s was to be in the company of some of the most notable men and women in American arts, letters, music, sports and politics. John Simon, the literary and film critic, told me once that he loved being invited to George’s parties, but the invitations has stopped coming. I asked him why and he told me this: “Invariably there would be someone at George’s party whose book or film I had savaged and they would take great umbrage at seeing me and would challenge me to a fight.” I think, Simon said, “in the end George just decided it was easier if I weren’t invited.”

A Dinner Party in New York

George told me once about a dinner party he had attended in New York City. At the dinner the guests played the following game:

What is the most normal thing New Yorkers do every day that you have never done?

One man said that he had never taken the subway. He said he had a fear of going underground. Another man said he had never been above a building’s third floor. He had a fear of heights.

But Plimpton won.

He had ridden subways and taken elevators to the top of the city’s highest buildings, but he had never chewed gum. Never, not once in his entire life, had he placed a stick of gum in his mouth. No Wrigley’s Doublemint for George, no Fleer’s Double Bubble.

He explained: In the home of Ambassador and Mrs. Francis P.T. Plimpton, children were forbidden to chew gum. Our parents, George said, thought it was socially déclassé, and thus we never did.

George in San Diego

On one of his many visits to San Diego to speak to The City Club, we were driving from downtown to my home, when George asked if I had I been to Africa? I said I hadn’t. He said, "Go, man, go! Sell your house if you have to, but go before it's too late!"

After returning from one of his many trips to that great continent, he came again to San Diego. He asked if I would take him to the zoo? That afternoon we went.

He knew something I didn't about the San Diego Zoo (that’s a redundancy, because he knew a great many things I didn't – and never will). He knew the zoo had a Bongo in captivity, and he had gone to Africa in search of that magnificent, but often elusive gazelle. Finally, in one of the zoo's many canyons, amid hillsides covered with towering Eucalyptus trees, against the slanting rays of October sunlight, we found the Bongo's enclosure. George then position himself so that I could take a photo of him standing, pointing over his left shoulder, at the Bongo in the background. (A photograph I now treasure.)

On one occasion George spoke at a dinner to The City Club of Los Angeles (which for five years was the third non-partisan public forum in my life). The next morning, after a breakfast meeting with some of Los Angeles’ top business leaders at the Century Plaza Hotel, we left late for a crew challenge that I had set up for George on Mission Bay in San Diego (he had rowed at Harvard). It was a promotion to help the San Diego Crew Classic, which each spring invites college crews from across America and abroad to come here and compete. He was to row against Jim Laslavic, a former Penn State All-American and NFL linebacker, who then, as now, covered sports for the local NBC television station.

As we drove away from the Century Plaza, I was mindful that we had 120 miles in front of us – and 90 minutes before the crew challenge. As I drove down Interstate 405, at speeds greater than an ostensibly intelligent person should drive, George asked if he could read to me from The New York Times? I said that would be wonderful. He proceeded to read story after story. One of the stories he read that day was about a town in Georgia that the actress, Kim Basinger, had bought. We thought that was pretty terrific, and agreed we wouldn’t mind owning a town of our own.

With the tolerance of higher powers and the California Highway Patrol otherwise engaged, we arrived in time for the big race on Mission Bay, which George decisively won, defeating with ease the younger, stronger, Laslavic (it’s always good when an ex-NFL player is humbled, especially by an older athlete). Afterwards I told my brother, Dan, how, as we drove down from LA, George had read to me from The Times. George overheard me and said, “Dan, the only reason I read to your brother was I was terrified of his driving, and by reading The Times I didn’t have to look!”

On one occasion he directed the San Diego Symphony. On a United flight out from New York he practiced conducting with a number six pencil, with head set in place, listening to the musical score he would conduct. He said he drew from his fellow passengers the most curious of looks. He practiced several times with the symphony, much to the distress of the real life conductor, David Atherton. On the night of the Symphony’s opening, Atherton took George aside and told him that he had instructed his musicians that under no circumstances were they to heed George’s movements with the baton. That Atherton had told them that George could not read a sheet of music and following him would be futile. The audience, unaware on Atherton’s directive to the Symphony members, thought George did a credible job. While Atherton may have had second thoughts about George leading his musicians, those of us who planned it as a special promotion for the Symphony, thought it one of the best things that ever happened to an organization often overlooked in the uncertain world of San Diego arts and culture.

On yet another occasion, a large black tie fund raising event to benefit one of San Diego’s charities, George agreed to act as an auctioneer. The organizers of the charity had hired a professional auctioneer, but it readily became apparent that the “amateur” was upstaging the “pro”. The hard truth is that George, amateur or not, was a brilliant auctioneer, and by his performance that evening he helped swell the coffers of a worthy charity.

It seemed like George would do almost anything, in his role as participatory journalist. On one more San Diego visit – he was to speak at a writers symposium at Point Loma Nazarene University – he asked if I would arrange for him to swim with Sea World’s Killer Whale, Shamu, the theme park's biggest attraction. Penny Masters, who handled public relations for Sea World, initially set it up, but at the very last it was decided that George in the pool with Shamu was too dangerous, and the swim wouldn't happen. He was visibly disappointed when I told him the Shamu gig was out. I also recall that the staff of The Paris Review was relieved when they heard the news of the cancelled swim.

George and Jonas Salk

George called one day and asked if I knew Jonas Salk, the inventor of the polio vaccine? I said I did. He then asked if I could arrange a meeting?

The purpose of the meeting George said was that he, acting in behalf of Esquire magazine, needed to determine what kind of Christmas gift Dr. Salk would like? This had become for the magazine a clever story line – what famous people wanted for Christmas.

In fact, the year before George had gone to Moscow to ask President Gorbachev what he wanted for Christmas?

George flew to San Diego and on a Saturday morning my brother Dan drove him to Dr. Salk’s La Jolla home. Dan left the two great men alone and went off to conduct some business of his own. Not long after I received a whispered phone call from George. Could Dan return and pick him up? I called Dan and said Plimpton needs you to come back. He’s finished with Dr. Salk.

I wondered why the Plimpton-Salk meeting had consumed so little time? Plimpton had told me how greatly he admired Dr. Salk, how he had long wanted the opportunity to meet him, and how grateful he was his gig with Esquire provided that chance. His wanting to meet Dr. Salk was not a surprise; of course, he had a livelong fascination with men and women of great accomplishment.

When George and I met later that day I asked why he left Dr. Salk’s so quickly? He had flown across the country to meet Dr. Salk and their meeting had lasted less than an hour.

He then told me that no sooner had he arrived at Dr. Salk’s home the great man began to show George his collection of crystal. He wanted George to see each item. He wanted him to know how he had come about obtaining the pieces in his extensive collection. This was too much even for George, a man of marked tolerance for others. He was deeply disappointed that Dr. Salk, a truly legendary figure of the 20th century, had so pedestrian a habit as collecting crystal. George was dumbfounded. He told me it had been one of the most disillusioning experiences of his life.

A Grand Dinner in Washington

You would have no occasion to know this, but for 18 months I worked with Denise Koptcho, the Social Secretary to the Ambassador of France, Francois Bujon de l'Estang, planning a dinner in Washington honoring George and The Paris Review. When I first called the Embassy, I was referred to Ms. Koptcho. I was, for me, slightly apprehensive, wondering how I would explain what I had in mind, a dinner tribute to George and The Review? I was reasonably certain that it wasn’t everyday someone called the French Embassy and suggested a dinner be held

But surprisingly, or so seemed to me, Ms. Koptcho knew who George was, and also knew of The Paris Review. I had no idea where this would go, but at least one important obstacle was out of the way – the social secretary thought it was a good idea!

When I told George what I had done, why I thought it appropriate for the French to do this, he was highly dubious. He said it will “never happen.” That element of doubt persisted almost until the night of the dinner. But I can be stubborn about things like this, and I kept working with Ms. Koptcho. Finally, after many months, I was told that George and I should come to Washington and meet with Ambassador and Madame Bujon.

The day before the meeting George called and asked, “Tell me again, why I am doing this? Why am I getting out of bed at four-thirty in the morning, hauling my aging carcass to La Guardia, in order to fly to Washington for a nine o’clock meeting? I don’t even know where I’ll have breakfast.” Like some of us, on occasions, George could be cranky. He was that day, but I said firmly, “You have to do this. It will be okay, and you will be able to find a place for breakfast.” I suggested the Madison Hotel, where his friend Ben Bradlee, the former Executive Editor of The Washington Post, often dines.

We arrived promptly at the residence for our meeting with the Ambassador and his wife, plus two cultural attachés, one from the Embassy in Washington, and the other from the French Consulate in New York. In a lovely room, with mid-morning sunlight streaming through the windows, George proceeded to entertain and charm the French officials, as only he could. After 50 minutes of George’s storytelling and the resulting great mirth, Ambassador Bujon said to George that it was time to decide what kind of party should be held for him and The Review?

He said they could have a lovely party in the garden, where several hundred people could come. It would be beautiful in the garden in late spring, he said, “the flowers will be in full bloom.” “Or,” he added, “we could have a dinner in the house for maybe fifty people, using one of the dining rooms, but if we were to use both, one hundred could attend.”

At this point, Madame Bujon asked, “Mr. Mitrovich, since this is your idea what do you think we should do?” I said I thought a formal dinner would be appropriate. Madame Bujon said she agreed. The Ambassador said, “Then it’s settled. We shall have a wonderful dinner for George and The Review.”

To which George responded, “Can we help you pay for it?”

I almost slipped off of the chaise lounge where I was sitting. I could tell the Ambassador was puzzled, as was Madame by George’s question, “Can we help you pay for it?” “Do you mean,” the Ambassador asked, “that we should have a fundraiser for The Paris Review? Certainly we could do that, if you wish.” After a moment or two of unease and uncertainty, I said that I thought there had been enough fundraisers for The Review, that we should just have the dinner. The Ambassador and Madame Bujon met my suggestion with visible relief. (It wasn’t quite true, of course, that there had been “enough” fund raisers for The Review, as there can never be when it comes to funding a literary quarterly.)

We said our goodbyes and started walking down Kalorama Road toward Connecticut Avenue. We were in search of a taxi to take us to Capitol Hill, where we were hosting a lunch for some members of Congress and media friends. As we walked I turned to George and said, in a voice born of puzzlement and wonder, “Can we help you pay for it!” What were you thinking, Plimpton?”

I knew this would be a very expensive dinner, and doubted whether The Review had money to underwrite such an occasion – and I knew with certainty neither The City Club nor The Denver Forum did. But I also doubted that the French Government, agreeing to hold a dinner for George and The Review, would expect help with the dinner tab.

The question George had put to the Ambassador and his wife, given the circumstances of his upbringing, was, I suppose, perfectly normal. In polite society one does that. To him the question seemed appropriate. I had a different reaction to it; but then my childhood was very different from George’s.

France’s Highest Civilian Award – The Legion of Honor

In June of 2002 the dinner finally took place. More than 100 people came in formal dress, including some of the nation's most powerful people, from Congress and the media, as well as two members of the United States Supreme Court – Sandra Day O'Connor and Stephen Breyer. Billy Collins, America's Poet Laureate, read a lovely poem written specifically for the occasion. Ilann Maazel, the son of the director of the New York Philharmonic and a brilliant pianist, played the music of Chopin.

In June of 2002 the dinner finally took place. More than 100 people came in formal dress, including some of the nation's most powerful people, from Congress and the media, as well as two members of the United States Supreme Court – Sandra Day O'Connor and Stephen Breyer. Billy Collins, America's Poet Laureate, read a lovely poem written specifically for the occasion. Ilann Maazel, the son of the director of the New York Philharmonic and a brilliant pianist, played the music of Chopin.

Following dinner the Ambassador presented George with France's highest civilian award – The Legion of Honor. The evening ended in the garden of the residence with a fitting fireworks display, choreographed by George, the “unofficial” Fireworks Commissioner of the City of New York. (Several days before the dinner notices had been distributed throughout the neighborhood alerting people that a fireworks show would occur. With Donald Rumsfield, the Secretary of Defense, living across the street, the Ambassador was anxious that the fireworks display, small though it was, in a town easily unnerved, not be mistaken for a terrorist attack.)

Until only a few days before the dinner, no one knew what the Ambassador had planned. George and I had talked about the possibility of the Legion of Honor being given, but neither of us thought seriously it would happen. (And the truth is, I never dared asked the Ambassador if it was possible. That seemed, even for me, a little too much.)

In Gratitude

I shall be, as George was, eternally grateful to Ambassador and Madame Bujon, to Denise Koptcho, for her critical role, and to the Government of France for giving George an award he treasured, I believe, above all others. (How odd that The New York Times, the “newspaper of record,” in its obituary about George, missed this salient fact altogether. But then they didn't cover the dinner, either.)

There is only one greater honor for George to receive – The Presidential Medal of Freedom. My hope is that President Bush will see the wisdom, posthumously, of conferring this award. George, a Democrat of abiding commitment, especially to the Kennedys, had a wonderful friendship with the Bush family, particularly with the President's father (or, number "41", as the Bush family refers to him)

Dinner Postscripts

There are two postscripts to the dinner. The first concerns the question George had put to the Ambassador on the morning of our meeting to discuss a tribute to both he and The Paris Review. The question was, "Can we help you pay for it?" Here's the meeting's denouement:

The residence of the French Ambassador, while one of the loveliest homes in Washington, does not contain a grand piano. One was required for Ilann Maazel. Thus a Maryland company was contacted for the purpose of providing the necessary piano. It did not come cheap. In the end The Paris Review paid for the rental. There was one other cost associated with the dinner, one involving VIP parking. A Washington company was hired, with my brother Dan paying the tab. So, in the end, "Can we help you pay for it?" was a more appropriate question to ask than I had thought.

The second involves the matter of the guest list for the dinner. The Ambassador had only two requests. He wanted the British and Italian Ambassadors included. Both were chums of his and Madame Bujon. But that was his only request. The rest was left to George and me. George had determined that few of his friends from New York would come down, so he focused on inviting his Washington friends, people like Ben Bradlee and Sally Quinn. But in truth his list, not unlike that of the Ambassador's, was quite short. So it was left to me to draw up the invitees.

Of all that happened leading up to that grand and glorious evening the nature of the guest list was to me the most astonishing, and, in the end, the most amusing. Astonishing because it had never occurred to me that I would be the guy who invited most of those who came to the dinner. Amusing because it strikes me as highly unlikely that a guy from San Diego, who had never played the Washington social scene, whose only true knowledge of it came from reading Sally Quinn in The Washington Post, should suddenly have such remarkable powers -- deciding who was in and who was out at a big, important Washington dinner.

In making up my list I began with the Justices of the United States Supreme Court. I quickly eliminated the Chief Justice, Mr. Rehnquist. I then dropped Clarence Thomas, Anthony Kennedy and Antonin Scalia from consideration. I determined invitations would go to David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, John Paul Stevens, Stephen Breyer, and Sandra Day O'Connor. What was the determinate? Oh, put it down to concerns about philosophical leanings and social compatibilities.

Of the members of the Court invited, Justices Breyer and O'Connor accepted. They brought to the dinner a grace and presence that was palpable. From what I observed, they had a lovely time.

I invited friends of mine from across the country, beginning with the Red Sox's Larry Lucchino, and his wife, Stacey. Congressional friends like Diana DeGette of Colorado and her buddy Darlene Hooley from Oregon were included. Abe Pollin, the owner of the NBA's Washington Wizards, whom I didn't know but admired from a distance, was invited. Friends in journalism, like syndicated columnist Marty Schram and Copley Newspapers' Washington Bureau Chief George Condon Jr., and others made the list of invitees. Friends from Denver, Doug and Hazel Price, as well as Carol Waltz, came. Tom and Jan Brunner came from South Bend. My brother Dan and his wife, Linda, came from San Diego. Dan's daughter, Marrisa, was also present. My wife, La Verle, was there, so too our son, Tim, and his wife, Lisa. In all, 102 people attended the tribute to George.

Carol Waltz called it, "The invitation of a lifetime”, a sentiment echoed by Doug Price. To Plimpton I was the “king of hyperbole," but as it relates to that evening, the reach of hyperbole exceeded my grasp. All I can say is – it was one great dinner party.

Trip to London

Several weeks after the dinner, George was in London. He was invited to a very fashionable party, where he met Roy Jenkins, a former leading member of the Labour Party. Jenkins noted that George was wearing, on the lapel of his jacket, his Legion of Honor Chevalier Ribbon. Jenkins told George that in England wearing a foreign award without the permission of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, was strictly forbidden, and had been, he added, since Elizabeth I (who had gotten weary of seeing her ministers in public weighed down with citations from foreign governments). George told me was so “intimidated” by Jenkins that he took the “damn thing off.” I laughingly told him it was unfortunate he had done that, since, as a citizen of the US, he was not subject to Her Majesty’s authority.

Our “Bush Problem”

He told me once of having been invited to Camp David for a weekend of playing tennis with the President. He said the President was in mid-toss on his serve, when a telephone, adjacent to the court, rang. The President dropped his racket, walked over to where the phone was, picked it up, and suddenly was seized with the most puzzled look. George thought to himself, "World War III." The President turned to him and said, "George, it's for you."

George’s friendship with the President began while he was writing for Sports Illustrated, assigned to cover the inaugural of a horseshoe court at the White House. Not surprisingly they hit it off well. George Herbert Walker Bush is a very likeable man. Subsequently the President would invite George to these tennis weekends at Camp David.

Before a luncheon at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in 1991– an event my brother Dan had arranged to honor Fred Lebow and the New York City Marathon – George said to me, "We have this Bush problem." I said, “What do you mean? He answered, "We're both Kennedy people, but we like this man." That was true, Kennedy loyalist, or not.

But he also told me that whenever he was invited to spend time with the President, his mother would remind him that he had a moral duty to tell the President he needed to be pro-choice. And upon his return his mother would call and ask, “George, did you tell the President what I asked?” She had given similar instructions to George’s father, Ambassador Francis Plimpton, when he had been sent some years back on a presidential mission to Rome to see the Pope. She had been insistent, George said, that the Ambassador discuss with His Holiness issues of women’s rights. His mother, he told me, was a woman of very strong character and opinion. No doubt.

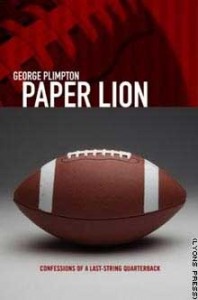

40th Anniversary of Paper Lion

When we spoke the day before he died he told me of having just returned from Detroit, where that weekend the NFL Lions paid tribute to him on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of one the best books ever written about sports – and the best ever written about football – "The Paper Lion."

When we spoke the day before he died he told me of having just returned from Detroit, where that weekend the NFL Lions paid tribute to him on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of one the best books ever written about sports – and the best ever written about football – "The Paper Lion."

At a dinner the night before Sunday's game, George said he saw 30 of his teammates from his playing days, however brief, as the Lions' QB – participatory journalism at its best, and most frightening level. Three of his Detroit teammates, he said, were in wheelchairs, but all had a wonderful time. He also told me that three of the players were in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. He said he was told after the dinner that the incident of Alzheimer in former football players is higher than the general population. (So many conversations I had with George over the years were similar to that. Suddenly, in the midst of a chat, you would learn some new and startling thing.)

At halftime of Sunday's game, George and his teammates were brought out to mid-field. Somehow the Lions had found his uniform jersey from 40 years ago – the one bearing number "0" on it – and presented it to him.

50 Years & The Paris Review

George's death came just a few weeks before The Paris Review's 50th Anniversary Party – October 14th at Cipriani in NYC. A festive night was planned in honor of The Review's founding editors – Peter Matthiessen, Harold Hume, Tom Guinzburg, William Pene du Bois, Donald Hall, William Styron, John Train, and, of course, George Plimpton. Now, with his death, circumstances were greatly changed – but the dinner was held, as George would have insisted; it became an unforgettable celebration of his life.

George's death came just a few weeks before The Paris Review's 50th Anniversary Party – October 14th at Cipriani in NYC. A festive night was planned in honor of The Review's founding editors – Peter Matthiessen, Harold Hume, Tom Guinzburg, William Pene du Bois, Donald Hall, William Styron, John Train, and, of course, George Plimpton. Now, with his death, circumstances were greatly changed – but the dinner was held, as George would have insisted; it became an unforgettable celebration of his life.

While the men listed above – then young and living in Paris, following their literary heroes – were involved in The Review’s beginnings, it is fair to say that absent George’s commitment these 50 years, The Review would not have seen 25 years, much less 50.

The offices of The Review are in the Plimpton family brownstone on the Upper East Side of New York City. There, an extraordinary staff, led by Brigid Hughes, Elizabeth Gaffney, Charles Buice, Tom Moffett, Fiona Maazel, Oliver Broudy, and Ravi Nandan, worked with George to insure The Review met its quarterly publication dates. This talented group of young men and women worked long hours, for little pay, but with a devotion to George and The Review that even the world’s worst cynic could not help but admire.

It should not be lost on people that The Paris Review, unlike the Georgia, Sewanee, Southern, Massachusetts, Gettysburg, Antioch, New England, Yale reviews, etc., has no college or university relationship, no vast academic institution to insure its survivability. It has existed these 50 years because of George Plimpton and the remarkable young people who, like him, made an unyielding commitment to its continued existence – and excellence.

There are many reasons why George Plimpton is one of my heroes, but the 50-year run of The Paris Review, is high on the list. My regard for his staff, some of whom I’ve gotten to know slightly over the years, is also very high. I am in awe of individuals who make such commitments, bear such personal sacrifices, in order that something the world barely notices can exist, as E.M. Forster once suggested.

The Last Gentleman

Now, perhaps more than ever, people will focus on what an extraordinary human being George Plimpton was, and on the greatness of his achievements – The Paris Review and his oeuvre of writing. In so doing they will see a person of consummate tolerance for his fellow human beings, of remarkable intelligence, of great energy and humor about life, and of an unyielding devotion and loyalty to his many, many, friends. (From Brooke Astor to Muhamed Ali, did anyone ever have more friends?)

Now, perhaps more than ever, people will focus on what an extraordinary human being George Plimpton was, and on the greatness of his achievements – The Paris Review and his oeuvre of writing. In so doing they will see a person of consummate tolerance for his fellow human beings, of remarkable intelligence, of great energy and humor about life, and of an unyielding devotion and loyalty to his many, many, friends. (From Brooke Astor to Muhamed Ali, did anyone ever have more friends?)

He was a person of transcendent goodness and decency, and those qualities must never be forgotten, for in the end they trump all others – whatever judgments his literary peers, a profession often consumed by jealousy and antipathy for their class, may make of George as a writer and editor.

On Christmas Eve, George and his family would attend a worship service at a Methodist church in Connecticut. He told me how beautiful he found those services, how inspiring the music, the reading of the ancient texts. I shall think of him often in such serene and reassuring surroundings.

I have been blessed with many friendships, but apart from my family, four people, in particular, have impacted me the most – Malcolm Muggeridge, the great British journalist and writer; Buck O’Neil, the Negro League legend, Robert F. Kennedy, for whom I was privileged to serve as a press aide in the Presidential campaign of 1968, and George Plimpton.

George was a lovely, lovely man. I shall miss him terribly. But the loss we feel, those who knew and loved him, must now be measured against a happier realization, that his was an extraordinary life.

We say our goodbyes upon earth, this sometime travail of tears – as it is now for George's family, his colleagues at The Paris Review, and his legion of friends the wide world over. But if you are a person of faith, you do so in the confidence that one day, in God's own time, we shall meet again – in a place not made with hands, where tears never fall, and the sun never sets.

For me it is best expressed in the words of an old hymn: "I will meet you in the morning, just inside the Eastern Gate."

George Ames Plimpton – 1927-2003. May his sweet soul rest in peace.